Augmented Reality Glasses

Designing for the Future of First Response

A police officer is patrolling a crowded street in downtown Boston. She’s surrounded by tourists, commuters, students, and workers on lunch break.

Suddenly, her smart radio pings an alert—there’s been an armed robbery in a jewelry store around the corner, and the suspect is fleeing in her direction, trying to blend in with the crowd. The smart radio transmits an image of the man she’s looking for, who already has an outstanding arrest warrant.

The officer activates her augmented reality (AR) safety glasses and scans the crowd of faces around her. To the passersby, her face doesn’t look unusual, but now she can see controls and information overlaid on the scene. In a few minutes, the glasses pick up a face in the distance that matches the image on her smart radio. It’s the fleeing robbery suspect. Signaling for backup, the officer begins to move toward the man she’s identified, as her glasses continue to track his movements.

1. Riding Along

Firefighters, EMTs, and police are doing increasingly complex work in a world where consumer technology is evolving far faster than the antiquated tools and systems first responders currently rely on. Lack of reliable communications, incompatible tools, and frustratingly slow digital information systems hamper responders’ ability to manage complex and dangerous situations and take advantage of citizen input, and can compromise safety. Today, smart devices, social media, and civic data are making life easier and safer for consumers. In partnership with first responders, Continuum spent a year looking to the future of technology, from AR to smart fabrics, to envision the responder toolkit of 2040.

It all began with eight-hour shifts riding along in Boston’s ambulances, fire trucks, and police cruisers. We saw everything from routine traffic stops, to a downtown house fire, to a bomb threat, to the aftermath of a shooting. We noted the gear and systems first responders rely on now (including many ingenious “DIY” solutions) and between calls we talked to firefighters, EMTs, and police officers about the tools that work, and the gaps where new technologies could help.

2. Workshops: "I Want a Heads-Up Display"

We also ran workshops with first responders and industry innovators to help these two populations (who had never connected directly before) understand the needs and possibilities for technology in the first responder space. Industry representatives demonstrated drones, traffic-analysis software, new protective fabrics, and more, while responders shared detailed accounts of challenging situations, from riots to a plane crash, to help us understand the intricacies of a large-scale response.

We asked responders at these workshops to contribute to a “wish list”: potential solutions and products that could improve their capabilities in the future.

The proposed solutions were interesting, but the reasons why responders wanted what they asked for provided even more insight into their needs and values.

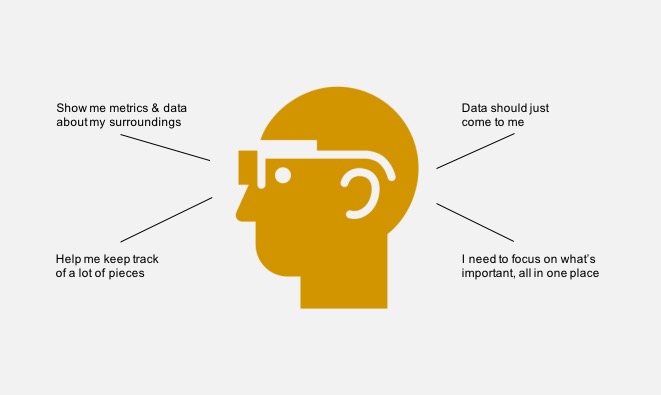

Despite concerns about safety, information overload, and distraction, police often asked for some kind of heads-up display to help them access information in context while on patrol. Our task was to figure out how to translate these needs into a product experience that would actually make sense for police in their daily work.

3. Concept Ideation

Knowing that current heads-up displays would not deliver the kind of seamless, fluid experience of providing information that police need, we began to explore future options. We looked at emerging AR products such as Magic Leap, the Meta headset, and HOLOLENS. Although in many ways this technology is still in the experimental stage today, knowing that AR is in development gave us confidence that our solution would be possible in coming decades.

Officers wanted a tool that would allow them to see critical information layered directly atop their normal view of the streets they patrol. Two big concerns from police steered our ideation: (1) avoid information overload; and (2) protect citizens’ and officers’ privacy.

We envisioned low-profile AR glasses to work in concert with other tools that are already part of routine policing workflows (smartphones, radios, earpieces). Data overlaid in real-time on what officers see would provide in-context data when it is most needed, and unify diverse data flows into a single, simplified interface.

4. Prototyping

We wanted to test whether police officers could use their future smart device in concert with the AR glasses in ways that were simple, helpful, and not disruptive to human connections on the street. To make that happen we needed to build realistic system elements that could give officers a good sense of how it would feel to wear the glasses, and how the digital tools that support them would function.

AR technology is developing fast, but today’s expensive devices are still not ready to deliver the seamless experience we envisioned. Instead, the team repurposed safety glasses to be our “AR glasses” and built a simple app on an Android phone (our “smart radio”) to simulate interaction with the system we imagined.

The Android’s built-in RFID-reader is easy to access for developers creating new apps–we combined this capability with some open-source code to simulate communication between the phone, a “smart badge,” and the glasses.

5. Testing

We didn’t need to create a true AR experience to get close to the kinds of interactions and use-cases we wanted to test. Instead, we shot some video around the city and added a simple interface, showing how data and controls overlaid on a live view of the scene might transmit information without distracting an officer from the interactions of the moment.

We gave officers our AR glasses prototype, and asked them to navigate the situation, occasionally checking for updates on their smart radio.

6. Testing Different Modes in Context

To make the test feel real, we needed to create a situation that would challenge participating officers to do what they do every day on the street—navigate obstacles, distinguish faces in a crowd, and share information with the rest of their team and central command. We wondered: How would officers most like to get this information? To find out, we played out the same scenario (hunting for a suspect with an open arrest warrant at a large Boston music festival) with three different tools: images sent via Google Glass, information transmitted via a wireless earpiece, and pictures and text via our AR glasses and smart radio.

Officers quickly rejected Google Glass and the wireless earpiece (both are distracting and prone to technical glitches, and officers felt that Google Glass would make it very difficult to interact normally with people they encounter). AR glasses solve many of these problems by overlaying essential information directly on the world as events unfold, highlighting faces and landmarks in context without blocking officers' field of view.

7. Refinement

Police who tested the AR glasses felt strongly that any heads-up display tool we created should in no way interfere with their ability to interact with people they encounter on the street. Face-shields, helmets, and even sunglasses can create an unacceptable barrier to one-on-one communication. Officers were also uncomfortable with our proposed universal face-recognition platform—they wanted to be sure that people on the street would not feel that their privacy was violated by random facial scans.

With this in mind, we created a form-factor that is as close to a “normal” set of glasses as possible (perhaps in the future some officers will want prescription lenses in addition to standard eye protection). We modified our interface prototype to simulate scanning only for faces in the crowd that match outstanding arrest warrants. The conversations around privacy and surveillance police started with us will need to continue as systems like this become real. Our aim was to keep the technology inside this system streamlined and minimally visible, knowing that AR displays of the future could make this solution possible.