Rita McGrath Wants You to Imagine Your Next Inflection Points. Now.

A Spirited Conversation with the Author of "Seeing Around Corners"

1. Columbia Business School professor Rita McGrath contends that understanding a company’s future resides at the furthest outposts of a company, and not necessarily in the boardroom. Organizational leaders must attend to employees out in the field: sales people, consultants, every stripe of frontline worker. Indeed, she incorporates a certain democratic strain to business strategy, in which picking up on distant early warning signals is essential.

“If you are one of those people on the edges, keep this thought: Your time may be coming sooner than you think,” she writes in her just-released book, Seeing Around Corners. “Sitting ringside at a change that is about to unfold can give you tremendous insight into what actions to take now, before the outcome is obvious to everyone.”

McGrath notes that competition makes some companies wake up to the necessity of listening to what people from all over their organizations have to say.

“If they’re still reporting up and in hierarchies and their competitors are able to move with more agility, they’re at a disadvantage,” she said in an October phone interview. “The competitive reality kind of forces a lot of them into it.”

To prepare for the future, she says that organizations must imagine, in detail, facing huge inflection points. In her book, she defines an inflection point as “a change in the business environment that dramatically shifts some element of your activities, throwing certain taken-for-granted assumptions into question” and adds that when “a system has a sufficient number of badly served constituents, an inflection point has fertile ground to take root.”

“Sitting ringside at a change that is about to unfold can give you tremendous insight into what actions to take now, before the outcome is obvious to everyone.”

As an example, McGrath writes that there’s a tremendous opportunity in hearing aids, for a company willing to invest in technical product development and human-centered design. She walks us through the regulatory, technological, and psychological reasons for the challenges here (she talks movingly about how her mother-in-law was so embarrassed by the noise her hearing aid made that she stopped wearing it during a visit). She mentions that FDA regulations toward hearing aids are changing and consumer costs are dropping. Finally, she concludes: “If we extrapolate from the statistic that only one in five people who could use help with their hearing have aids today, the market size in short order could be five times greater—perhaps as big as $40 billion—after the inflection point that allows anybody to get a discreet, self-adjustable hearing device.”

2. McGrath is right that the future will be won by those companies that are integrated and nimble. Such an operational model allows for self-willed transformation. For being proactive instead of reactive. “The great entrepreneurs and innovators… don’t just allow an inflection point to happen to them,” writes McGrath. “They connect emerging possibilities, deepen consumer insights, and explore new technologies to spark the changes that can get them—and keep them—on top.”

The holistic prescription is admirable, and one we follow at EPAM Continuum. In fact, we have a group called NXT that is all about thinking holistically of the future. As Kevin Young, Senior Director of Client Engagement, describes it: “NXT is obsessed with the future—constantly looking for lead indicators that will predict future scenarios. NXT does this by exploring culture, business, and technology trends and weaving together the seemingly disparate data points that ultimately create larger movements we call shifts.”

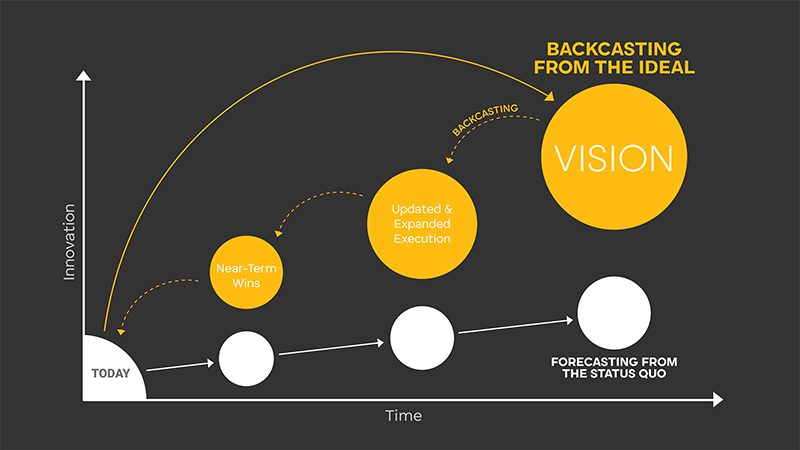

But the truth is, not every business is prepared to connect all these elements and then shift, even when the will is there. Part of the challenge is that many companies are insufficiently investing in imagining the various futures that might await them. Many organizations, McGrath said, “envision one future and they go charging after that future.” She advises taking a boarder view of things, encouraging readers not to think about industries but in the wider category of arenas, in which “you have to be able to entertain multiple potential futures simultaneously.”

McGrath illustrates this, in Seeing Around Corners, by providing some frameworks for scenario planning. In the book she shares a set of matrices that mapped out, for an energy distribution company she had worked with, two future possibilities: one in which a centralized grid dominated and one which was ruled by decentralized networks that relied on solar and wind power as well.

The key point: it’s as important for companies to think about positive future states and how to reach them as it is about catastrophes and how to avoid them.

3. McGrath seems to understand what’s motivating today’s business leaders, and it’s not fear. “I think there’s a lot more, almost, humility in realizing what got you on top may not keep you there,” she said. This humility guides these companies to be perhaps less emotionally attached to certain historical business models, marketing techniques, or even work processes, and to invest in, and continually test for, what works.

Dairy industry person says: "We didn’t realize that coconuts, wheat, and oats are doing the jobs we were once hired to do.” McGrath comments: “It’s a classic case of ‘Because they’re not dairy, we didn’t see them on the competitive horizon…’"

“The idea of humility is just being able to acknowledge that things may change—and that may not serve you well in terms of your current model.”

Her injunction, in Seeing Around Corners, for companies to “avoid denial” is interesting. “Leaders turn a blind eye quite deliberately because it is just more convenient not to take in news that things might be changing,” McGrath writes. In the book she quotes the denial of Rand-McNally’s former CEO, Robert S. Payoff (in a 2006 interview he says: “There’s going to be some changes in how [maps] are used, but people will still want to open them and read them with their coffee”) and then concludes: “Rand McNally was acquired by distressed-asset firm Patriarch Partners in 2007.” It’s hard to imagine many contemporary business leaders reading that section without a squirm of recognition.

4. I wondered if, since publishing the book, McGrath has noticed any new systems with badly served constituents. Unsurprisingly, the answer is Yes. She recounted, for instance, attending a recent meeting of the U.S. Dairy Export Council.

“We were talking about ‘jobs to be done’ and one of the people at the meeting said: ‘We didn’t realize that coconuts, wheat, and oats are doing the jobs we were once hired to do.’”

This would have been a terrific case study for Seeing Around Corners (and it puts one in mind of how the big meat companies saw the threat of plant-based protein, and are now getting in on the action). McGrath said: “It’s a classic case of ‘Because they’re not dairy, we didn’t see them on the competitive horizon…’”

It’s extremely hard to see what’s beyond the competitive horizon. In this continually disruptive world of ours, it does no good to wait passively for change to happen. And because of this, innovation is becoming everyone’s business.

Previously, McGrath said, there was always a distinction in business thinking. “‘Oh, we think one way when we’re doing the core and we think another way when we’re doing new business.’ I think what we’re gonna see, increasing over the next 15 years, is this way of thinking is going to become the way successful businesses operate. This integration of how you think differently is not gonna be confined to new business anymore; it’s going to be part of what all of us have to do!”